A Necessary Ruin

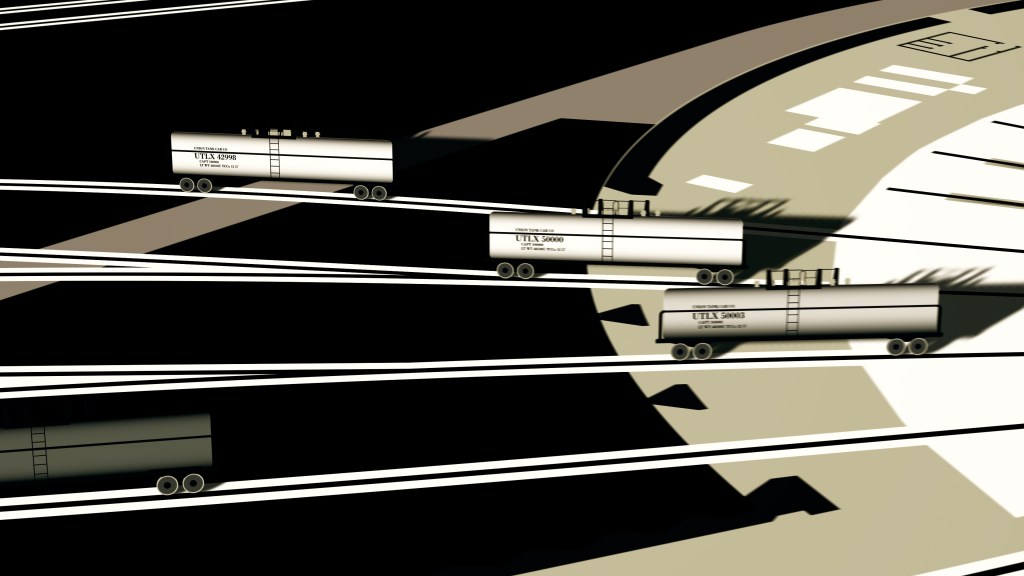

When it was completed in October 1958, the Union Tank Car Dome, located near Baton Rouge, Louisiana, was the largest clear-span structure in the world. Ostensibly designed by the visionary design scientist and philosopher Buckminster Fuller, this geodesic dome was, at 384 feet in diameter, the first large scale example of this building type. A Necessary Ruin relates the compelling narrative of the dome’s history via interviews with architects, engineers, preservationists, media, and artists; animated sequences demonstrating the operation of the facility; and hundreds of rare photographs taken during the dome’s conception, construction, decline, and demolition. The film was funded by a grant from the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts.

INTRODUCTION Evan Mather

I have always been interested in ruins. In the early 1990s, when I was studying landscape architecture at Louisiana State University, I came across J.B. Jackson’s essay “The Necessity for Ruins” – a passionate argument for their presence in the landscape – specifically their significance in giving meaning to a place. Shortly after reading this, faux reconstructed ruins began to turn up in my projects.

In early 2004, and now living in Los Angeles, I began working on a short film about Baton Rouge. Part travelogue, part autobiography, Scenic Highway would introduce the viewer to the city, show off a few of its attractions – notably Huey Long’s art deco State Capitol building – and take side trips to New Orleans and India. Growing up in Baton Rouge, I had heard little bits and pieces – rumors really – about a huge, futuristic, geodesic dome, hidden in the woods, somewhere north of town. This was the Union Tank Car Dome – ostensibly designed by Buckminster Fuller and colloquially known as the “Bucky Dome”.

During a trip to Baton Rouge in October 2004, I found the dome (which actually was pretty easy) and spent a few minutes filming the facility. I was particularly fascinated with the deteriorating condition of the building – this was supposed to be a world famous piece of architecture – and here it was, a genuine ruin, rusting away in the wilderness.

This footage formed the basis for the final chapter of Scenic Highway in which I made the case that of all the things to see and do in Baton Rouge, the dome was the most special – it was “hidden treasure” and represented the true meaning of the place.

When the dome was torn down in November 2007, I decided to make A Necessary Ruin not only as homage to the structure itself, but also as a tribute to the community that made it possible.

A Necessary Ruin was primarily filmed over three trips I took to Baton Rouge in 2008 and 2009 during which I conducted most of the interviews. Shot primarily in high definition digital video using both Canon VIXIA HV30 and Flip Mino HD cameras, it was edited on a Mac Pro workstation running Final Cut Studio 2 and After Effects CS4. SD sequences were shot using a Canon Optura 40 and a Chinon 132P XL Super-8 camera on Kodachrome 40 Type A stock. Both were upconverted using Red Giant Instant HD. The score was composed and sequenced in using Steinberg Cubase, Propellerhead Reason, and Noteheads Igor Engraver.

The typefaces are Berthold Akzidenz, Bodoini Poster and Clarendon.

AN UNNECESSARY LOSS Matthew Clayfield

Towards the end of Scenic Highway, Evan Mather’s semi-autobiographical and wholly-heartfelt paean to Baton Rouge, Louisiana, the viewer is instructed to “start at the State Capitol Building and head north eleven miles along Scenic Highway, past the chemical plants and storefront churches, take a left on Brooklawn, head about a mile-and-a-half, and park your car”. Only several hundred feet away, he is told, he will come across R. Buckminster Fuller’s Union Tank Car Company dome. “Ignore the guard shack, barbed wire and ‘No Trespassing’ signs,” the narrator intones. “This is architecture.”

Or at least it was. Within twelve months of Scenic Highway’s completion, Kansas City Southern, the dome’s then-owners, secretly had the structure demolished In the interest of so-called “neighborhood improvement” – a euphemism in this case for cultural amnesia, and a term that one should always be wary of when spouted by anyone with a profit motive – rendering the footage included in the film among the very last ever shot of what was, and should have remained, an architectural landmark.

More than a footnote to the earlier scene, A Necessary Ruin is a full-scale elaboration on it. It details the history of the dome from conception to destruction, makes a passionate argument for its cultural significance, and laments the all-too-familiar inability of the short-sighted to recognize or appreciate the visionary. It also seeks to “rebuild” the dome using all that we have left of it: the few flickering fragments of film and video, those faded archival photographs, that have, as these things so often do, outlived the rather too ephemeral reality they were enlisted in the first place to record.

That Mather should attempt such a project is hardly surprising. His work has always been characterized by a sense of nostalgia, both for the iconography of times gone by and for the mediums—namely, Super-8 and audio cassette—on which those times were captured. More recently, his films have paired this nostalgic bent with a personal rumination on space and place, as well as on the fluid and fascinating relationship between the two.

Of course, to some extent this rumination has always been an aspect of Mather’s work. Certainly, his fascination with the aesthetic potential of maps and topography– characterised most commonly in his films by the trope of the superimposed roadmap – was apparent to even the most casual observer as early as Vert and Fansom the Lizard. But since The Image of the City, Mather’s absurd reworking of Kevin Lynch’s urbanist tract of the same name, the image or figure of the map has become increasingly central to his work, taking on a level of meaning that it didn’t in the earlier films. (At the end of Scenic Highway, he even credits himself with “cartography”.) What Mather seems most interested in now is that singular point in one’s experience where a space suddenly transforms itself into a place, and what happens to the latter when the former changes, or is changed, for the worse. The maps in Mather’s recent work are less the colorful overlays of his earlier films as they are psycho-topographical palimpsests of places that once were but are no longer.

Mather is a filmmaker who likes to remember those things more often forgotten. The bedtime stories improvised by one’s parents when there wasn’t a storybook to hand. The mall that was knocked down that time to make way for a bigger mall. That he extends this willingness to remember, here, to a decrepit old object of esoteric high culture – and without his usual falsifications and attempts at spinning history anew – clearly speaks to the sense of loss he personally feels at the passing of his subject. The Union Tank Car Company dome may not have been built, as Professor J. Michael Desmond puts it in the film, to be “intentionally meaningful,” but then what is nostalgia if not the memory of that which was unintentionally so? If A Necessary Ruin is more mournful than Mather’s other films, it is perhaps for this very reason. Baton Rouge’s “Bucky Dome” was as unintentionally meaningful as the loss of it was unnecessary.

Matthew Clayfield is a journalist, critic, screenwriter and playwright currently based in Sydney, Australia.

[Evan Mather’s] riveting new documentary A Necessary Ruin … manages not only to make engineering sexy and preservation politics compelling, but succinctly tells the tale of one of the most tragic architectural plunderings in recent memory.

The Architect’s Newspaper

Mather’s film [A Necessary Ruin] sounds a cautionary note about imperiled modern-era structures and the often prohibitive costs of maintaining them.

“Demolished Bucky Fuller Dome Subject of New Documentary”, Architectural Record, 4/29/2010

2009

Short

U.S.A.

English

30 minutes

Evan Mather